So here we go with part two in our continuing saga. Thanks for the comments, a few of which I will respond to now.

Yes, everything in column 1 is true. It might be easier if I made it up, but probably not as interesting. I’m assuming that question was prompted by the Pete-Townshend-hitting -Abbie-Hoffman-with-his-guitar-incident. Pete mentions it in “The Kids Are Alright” and there are lots of references on the web.

Someone else flatly stated “Why do you want to talk politics? Politics has no place in music.” Well, that’s, um, what the whole column is about. Not partisan politics but rather social action. And I’m writing it because I have such immense respect and awe for the integrity of the jam – the purity of that place – so this is in no way a political polemic or screed – (as Mr. Dylan observed, it’s pretty desolate when “everybody’s shouting out ‘Which side are you on?'”) – but an exploration of the intersection of that holy pure place – with the worldly realm in which we all also exist.

(It’s like Kazantzakis’ metaphor of his novel “The Last Temptation of Christ” – that struggle we all face between our spiritual and earthly selves).

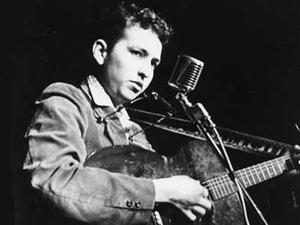

As I see it, in music there are broadly two connections to direct social action. First is overt political action, literally embodied by Woody Guthrie’s slogan of “This Machine Kills Fascists” scrawled on his guitar. Guthrie pulled no punches in his protest songs, although American culture saw fit to remove his socialist bite so it could assimilate his myth into its harmless mainstream, just as it did Mark Twain and John Steinbeck.

Woody Guthrie: harmonica, acoustic guitar, and no fear of the big statement

Bands flying Guthrie’s flag through the years – whose raison d’etre is pointed social critique – stretch across the genres – from folk to punk to reggae to rap to arena rock. Big-name purveyors outside of the usual hippie suspects include Steve Earle, The Clash, Rage Against the Machine, Bob Marley, Public Enemy, Pink Floyd, and U2 (and most recently, the current releases from the Beastie Boys and Green Day, “To the Five Boroughs” and “American Idiot”).

The Clash (“the only band that matters”) – also not timid about the big statement, circa 1980

Still, when you consider that Guthrie was Bob Dylan’s role model and the extent to which Dylan shaped the burgeoning musical scene of the 60’s – even the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix (and the Dead, obviously) admired him – you realize that even the roots of the jam are connected to music as social comment – as alternative to the status quo.

A baby-faced Bob Dylan – (see Guthrie, above) – shaping the 60s

And that’s the second connection – the jam.

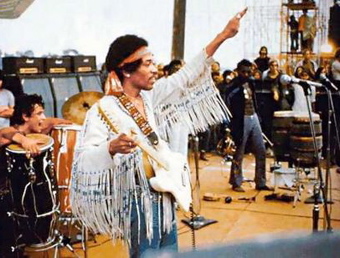

Hendrix is a great bridge between the unbridled jam and social context. No one would accuse him of musically limiting himself yet he carried an obviously strong sense of social purpose and ethics, both in his Dylan covers and his own lyrics, but maybe perfectly encapsulated in his all-instrumental “unorthodox” (Dick Cavett’s description) and “beautiful” (Hendrix’s description in response to Dick Cavett) rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner.” It’s a jam and it has meaning, weight and power beyond the guitar mastery because of it’s context. (Hendrix expresses an even trippier sense of his music’s social meaning in a scene from “Rainbow Bridge” – which I know I’ll get to in another column…)

The jam as political: Woodstock, 1969

But now, let’s… get back…to the Beatles. While John Lennon was not an instrumental virtuoso like Hendrix (his own evaluation of his guitar playing : “I’m not technically good, but I can make it fucking howl and move”), he pushed sonic boundaries both with and without his guitar – think of the sound collage of “Revolution #9” and his primal screams on songs like “Mother” from his first solo record, “Plastic Ono Band.” This record also includes the virulently political “Working Class Hero” and, looking at his whole career, it seems to me his peak experiences (1000 acid trips by his own estimation – although at that point, how reliable is his own estimation…) were a quest for a fulfilling way to live, leading to extremely Right Action-y sentiments like “All You Need is Love,” “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “Instant Karma.”

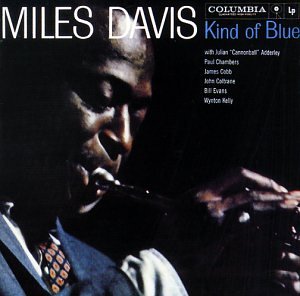

But you don’t even need to stray that far from the music itself. Forget lyrics. It’s (ahem) the jam that matters. Consider the purity of the jam on Miles Davis’ seminal record “Kind of Blue,” unofficially the best-selling jazz album of all time. Striving to rescue melody and feeling from the frenetic jazz of the time, Miles simplified his charts and focused the improvisations on careful responsiveness and sensitivity by recording the sessions in pretty much all one take with no prior rehearsal. Pianist Bill Evans’ liner notes are elucidative – comparing this deliberate form of improvising musically with a certain style of Japanese painting on thin parchment paper which will rip if you don’t paint with a clean clear stroke. “Direct deed is the most meaningful reflection” he concludes. Right Action.

Direct Deed is the most meaningful reflection

Bill Evans

If we could only jam with existence…

Yet isn’t that one of the most profound things that music has to teach? To truly jam, you need to feel where you fit into the larger picture – you need to find the larger picture with the other musicians until you become a vessel for it and the jam is greater than the sum of its parts and the sounds you make are not your own puny ego but the sounds of the universe – and you are not your own puny ego anymore either – you don’t question your next noise – it’s all one and it’s all right action.

And maybe you can carry that offstage.

Lay down all thought surrender to the void

It is shining…

Love is all and love is everyone

It is knowing…

Play the game existence to the end

Of the beginning

Of the beginning

To be continued…

(wherein, yes, I will get down to some more specific, flesh and blood, real-world applications again…)

Thanks for the feedback – comments and questions are appreciated.

And check out Bill Evans’ original handwritten liner notes here…