Nirvana in the Heart of Darkness

by Jeff Zittrain

Originally published in The Chabot Review, Spring 2004

“Mistah Kurtz–he dead”

T.S. Eliot’s epigraph to The Hollow Men, quoting Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

I’ve traveled into Cambodia and reached the Heart of Darkness where I find Kurt. But, unlike Conrad’s famous archetypal madman whose “preeminent gift of expression” is dying with him in the jungle, this Kurt is already dead, while his expression lives on. The “Heart of Darkness” is a bar in Phnom Penh, and “Kurt” is Kurt Cobain as Nirvana’s “Nevermind” cranks out of the portable tape player on the wall. It’s the end of May 1994 and his suicide is still fresh, committed just one month before. And I sit at that bar feeling the sweat running down my back and drinking a draft beer and watching his music assume the role of soundtrack to the struggling country as a few scattered patrons shoot pool, or sit at stools and tables in the small, dark room. The combination of the closeness of his suicide and the persistent mind games you go through spending a week in the lawlessness and confusion of Cambodia, spark with the effects of drinking beer in the tropical heat, to impart a sudden swirling synchronistic significance to the scene that might otherwise seem…melodramatic.

The bartender, a Cambodian of about 22, speaks quite reasonable English when I ask him about the situation in his country.

“No good tourism” he says, gesturing at the few patrons.

“Why is that?” I ask, even though I know.

“Khmer Rouge… Everyone scared to come here.”

“How’s Siem Reap?” I’ve been asking everyone about the town in northwestern Cambodia a few kilometers from the famous Angkor temples, the country’s biggest tourist incentive. I wanted to go there, but I’d heard conflicting reports of vicious battles in the area between the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Army, of an entire Army outfit dying in the town after eating rice boiled in Khmer Rouge- poisoned water, and of the nearby town of Battambang switching control weekly between the two sides.

“I think it is okay” he says. “Much army around there.”“How about the beach?” Although this had been popular for travelers as a day excursion from Phnom Penh, in the past month three Westerners (British and Australian) had been kidnapped while driving there, and not heard from since.

“Go to Siem Reap” he says. “There are nice beaches in Vietnam.”

Like most Cambodians I’d met, he wore a broad smile during this whole conversation, and while I sweated in the nighttime heat and drank beer, he showed me pictures of the Heart of Darkness from a year ago, filled with happy patrons, and of himself touring Angkor. The color touristy photographs seemed like an anomaly in what appeared to me to be a decimated city. The bar was small and dark, its high walls painted black, befitting its name and any number of punk bars you might find in the States, but also befitting Phnom Penh itself: the capitol of Cambodia is pitch black and empty after sundown, with no streetlights and no neon signs, its stores and houses closed and ominously chained. We got to the bar on the backs of sputtering motor scooters, rattling over dark, unpaved, muddy streets. It was achingly hot, even at night, and the fans stopped when the generators broke down, which occurred a few times each day. At these times there was nothing to do but sit in the shade and mop the sweat with your Khmer scarf and guzzle bottle after bottle of water and think about how hot you were.

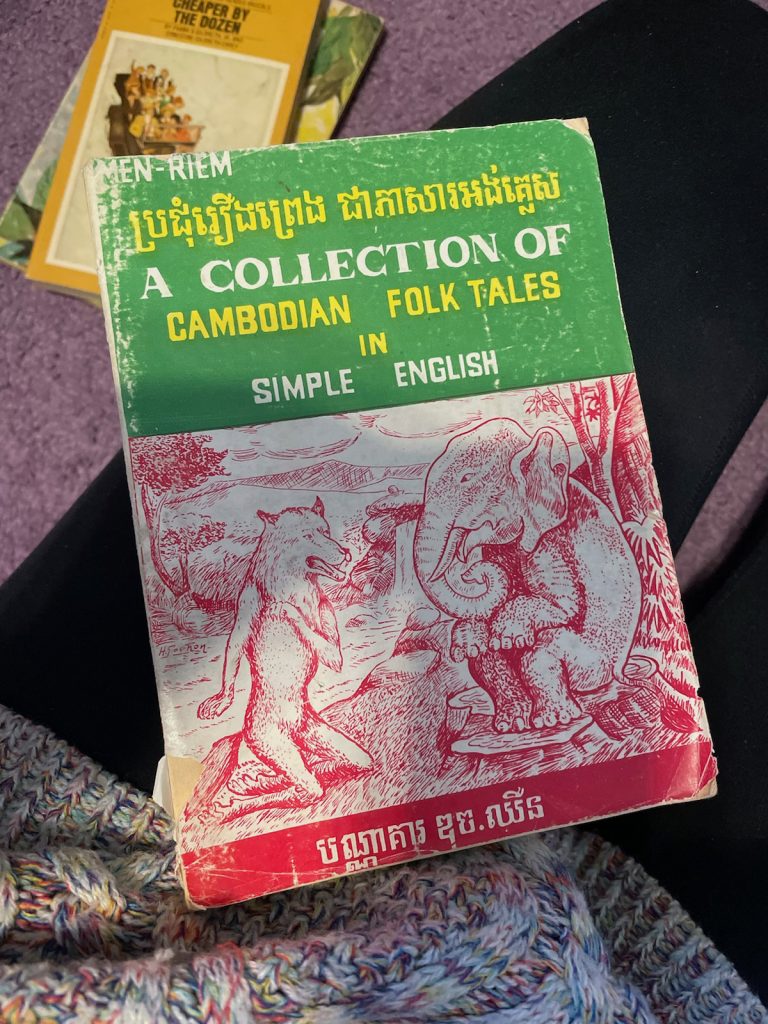

You could always find at least a few travelers doing just that at a cafe called “The Capitol” where ten-year old boys walk from table to table selling photocopied editions of the same four books about Cambodia. I walked into The Capitol on my first day in the country and bought a collection of Cambodian folk-tales for my nieces, but only bargained down to four dollars from six, and was thereafter besieged by the same kids every day I went in there. My bargaining skills improved, but by the time I left a few weeks later, I’d bought another copy of the folk tales, plus a book on Angkor and some post cards. The relative value of currency becomes obvious to any traveler moving from country to country, but when you go to Cambodia, the void of relativity widens, as you find yourself haggling over twenty cents with a kid who probably supports his family this way.

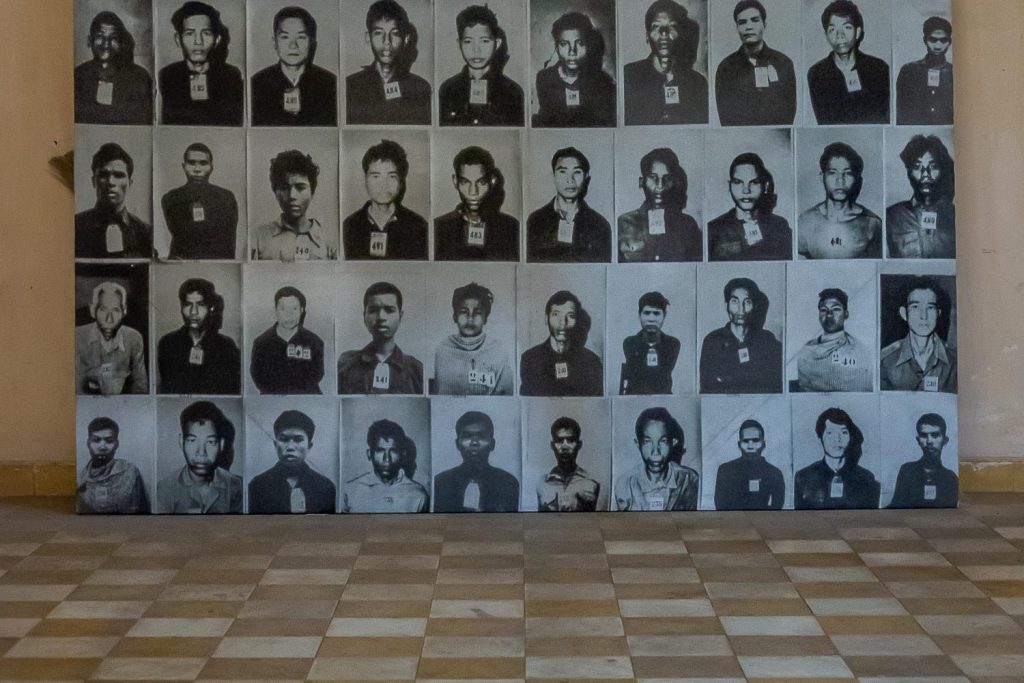

Although big-bucks tourism is practically nonexistent because of the country’s instability, even budget backpack travelers have more money than the average Cambodian. Naturally, the Cambodians try to make use of this, and one wall of The Capitol boasts large, white, hand-lettered signs announcing prices for tours of the city, the main attractions being “The Killing Fields” and “S-21”. “The Killing Fields” are mass graves about 15 kilometers outside of town where the only building is a tall glass temple filled to the top with skulls categorized by age and gender. Most of the victims were brought here from “S-21”, the lycee-turned into a prison/torture chamber, where the Khmer Rouge killed as many as 100 men, women, and children per day between 1975 – 1979, while, relativity lesson again, I was growing up in Pittsburgh worrying about the Steelers making it to the Super Bowl.

It wasn’t necessary to arrange these tours through the cafe, however. The cardboard signs on the wall create an everpresent backdrop to any meal or conversation you’re having in The Capitol, but the words hang over all of Phnom Penh. Interactions with other travelers or Cambodians will eventually hit upon visiting S-21, and scooter drivers approach you unsolicited all the time, trying to convince you, like used car salesmen, to let them take you to the “Killing Fields.” And after you’ve visited these places, and seen not only the brick cells and blood-stained floors, but the individual photographs taken of each victim before they were killed, which cover a few walls of S-21 like a high school yearbook, you can’t help but feel their sad eyes still watching their fellow countrymen, surviving relatives, and even travelers like yourself, walking the streets of their battered town today.

Phnom Penh is still reeling from its past, as if those blows of history were strong enough to leave it shaking for twenty years. Reaching beyond the obvious, the beggars and the war-maimed wandering the streets, there’s a certain implicit odd lack of balance; this first presented itself to me right after I bought the folk-tales on my first day at The Capitol. A German man of about 25 came over to our table to invite the woman I was with to a party, and as I stared at his back two of his friends casually dropped a huge bag of uncleaned pot onto our table. We accepted a map with directions to his house, and also, inadvertently, the bag, since it was still lying there when he got up. We held it up as he walked out the door but he waved it back to us. Almost immediately an older American, not the typical hippie traveler I’d generally seen, but heavy-set with a moustache and thick build that made him look like Dick Butkus, and whom I’d noticed watching us during the conversation, came over and sat down.

“Is that marijuana?” he asked.

As it was my first day in Cambodia after a few weeks in Malaysia, where signs with skulls remind you that possession of drugs carries the death penalty, I did not answer immediately. He was reaching into his money belt, for what I hoped was not a badge, but he only produced a paper, asking “Mind if I roll a joint?”

We told him he could just get a huge bag quite easily, from vendors in the street or at the stalls in the outdoor market, but he was interested in talking as much as he was interested in the pot. He was a Vietnam veteran who now lived in Hue, Vietnam, and he had adopted a Vietnamese girl as his daughter. When we asked how he liked Hue, he replied that he had seen a lot of friends killed there. I was interested in the healing process that seemed to be taking place, and was about to ask him about it, when he mentioned he wished the war were still going on. Not knowing how to respond, I said nothing until he asked where we were from, and, having moved to Berkeley from El Cerrito a few months earlier, I’d been proud my whole trip to be able to answer that question with a place people had heard of.

“Berkeley?” he practically shouted. “That shithole!”

This was not the reaction I was used to and it caught me off guard. “Well…” I began, “ there are problems with…”

“Fucking hypocrites!” he interrupted. “Hanoi Jane, Slick Willie, Tom Hayden! Fuck them all!”

This string of associations went on like an alcoholic’s does, building and losing intensity in what seems a random fashion but is actually a cycle of waves, and has nothing to do with anything the listener says. It became unnerving, feeling like a target with no control over stray outbursts. After about fifteen minutes, we left him with our bag of pot as we retreated back to our guest house.

This scene, along with the sight of an uncovered plain wooden box casually filled with human bones that stared at us from the center of a bright, off-limits room we’d stumbled into in S-21 were replaying themselves in my mind as I sat in the Heart of Darkness listening to Nirvana. Choruses exploded out of quiet verses the way bones and pieces of clothing came out of shallow graves in the midst of breathtakingly beautiful scenery at the Killing Fields. Something was lurking just under the surface all the time in Cambodia. It popped up in random outbursts, but after a while you could begin to sense it everywhere, just as Conrad described the absurd disparities of Colonialism seeping into Africa, and just like I would encounter the disparities involved in the opening up of Vietnam when I took a bus to that country a few weeks later. In Cambodia, the history was so heavy, yet so unresolved. What was going on, even now?

The people seemed almost equally upset by the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Army, for instance. There were also negative feelings with the Vietnamese even though they overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979. And through all the severe political upheavals there’s been a bizarre consistency in Norodom Sihanouk’s continual returns to power for over 40 years, ever since 1953. Yet despite the seemingly endless turmoil, coupled with so much recent terror and tragedy, the people I met were extraordinarily hospitable and easygoing. The surprises popping out at you put you somewhere between a fun house and a haunted house, where you’re not sure whether to laugh or be terrified or both.

This feeling seeps into every aspect of life in Phnom Penh, even the sheer lunacy of everyday traffic, which includes all manner of scooter, rickshaw, motorcycle, people on bicycles much too big or too small for them, little kids, old people, whole families of five piled onto one scooter, monks on scooters, and no traffic lights or laws or helmets; it sometimes felt like a Dr. Seuss cartoon. The only way to cross the street on foot is to walk calmly into the mass of traffic at a completely steady pace and let the speeding vehicles maneuver around you. If you try to slow down or speed up to avoid them, you will almost certainly cause an accident; it’s like a Buddhist lesson in letting go.

The Cambodians are generally brilliant drivers in this anarchic environment, and there’s a feeling of fun, excitement, and acceptance of everybody as they all make room for the diversity of vehicles; I once watched an 8-year old kid determinedly wobbling on a bike three times too big for him by painstakingly pulling up each pedal with his toe every time it went down and then stepping on them, one at a time, since he couldn’t reach to make a full revolution. He was doing this in the middle of daytime traffic, occupying his own dignified place amongst the fancy speeding scooters, and occasional cars and trucks, looking like an advertisement for the empowerment of the individual and the self-made man. Yet just as you let go and enjoy the freedom, you might come across an accident, as I did the very next day, with the victim put into the back of a passing rickshaw, crying with blood running down her face, rattling off to impoverished medical facilities.

The country’s tragic legacy and danger is in fact the big tourist attraction, evidenced by the preponderance of “Killing Fields” signs, and the name of the bar I was sitting in (as I would later sit in the “Apocalypse Now” bar in Saigon). You can’t fault the people for needing to make money. Yet if these films were attempts to depict the reality of the situations in these countries, and terrible, bloody situations at that, wasn’t it strange that now the countries were attempting to become like the films? It was like mirrors reflecting mirrors: The movie and the real place, The Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Army… North Vietnam, South Vietnam…

I looked through the box of tapes at the bar and asked the bartender to play the one Grateful Dead tape they had, “Skeletons from the Closet”. It was hopelessly out of place. The Dead’s mystic vision, that under the surface of everything is some sort of sparkling sense that it’s all okay, seemed to have nothing to do with the people shooting pool, or the smiling bartender, or the dark, hot city outside, with the scooters imploring you to go to the Killing Fields. No, Nirvana seemed to have it on target. Their melodicism keeps them pop, keeps the bartender bouncing jovially behind the bar, but it carries a sinister knowledge — of rage, sadness, and, above all, pain — that I could also see behind the happy-go-lucky attitude of Phnom Penh. Unlike the artwork on the Dead tape, their skeletons don’t smile.

Yet there was something more important, an added irony I could sense but not satisfactorily pinpoint. The raw tragedy these people have gone through for generations would seem to belittle the existential problems of the developed world, yet here they were dancing around to the music of someone who’d killed himself with a shotgun just a few weeks before. And, unlike the touristy photographs, it fit.

When I returned to the Bay Area, I read Michael Herr’s Dispatches, in which the hallucinatory absurdities of the Vietnam war seem to afford that entire generation of Americans a visionary experience similar, I thought, to the one that Conrad describes at the end of Heart of Darkness:

“…a passage through some inconceivable world that had no hope in it and no desire. I found myself back in the sepulchral city resenting the sight of people hurrying through the streets to filch a little money from each other, to devour their infamous cookery, to gulp their unwholesome beer, to dream their insignificant and silly dreams. They trespassed upon my thoughts. They were intruders whose knowledge of life was to me an irritating pretence, because I felt so sure they could not possibly know the things I knew. Their bearing, which was simply the bearing of commonplace individuals going about their business in the assurance of perfect safety, was offensive to me like the outrageous flauntings of folly in the face of a danger it is unable to comprehend. I had no particular desire to enlighten them, but I had some difficulty in restraining myself from laughing in their faces so full of stupid importance. I daresay I was not very well at that time.”

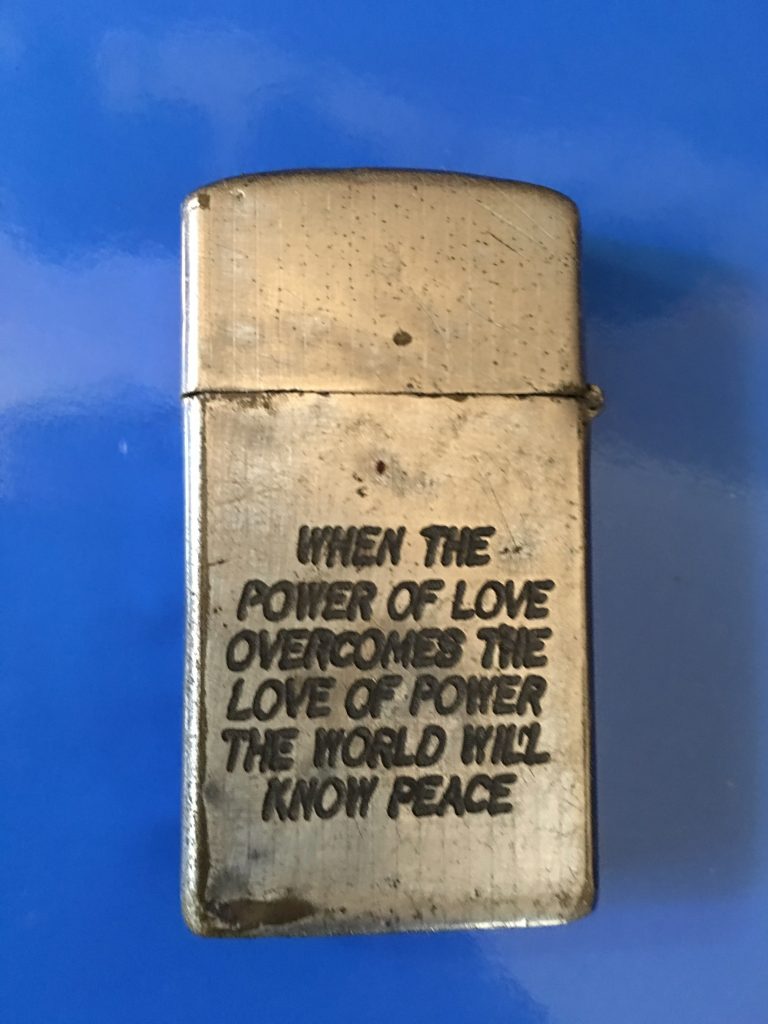

This, it seemed to me, was what Nirvana sounded like in that bar. But even more so; Nirvana in Cambodia added another level to Conrad’s critique of a shallow society. West met East at the juncture of the band’s name, paradoxically describing the transcendent release afforded by the expression of truth, no matter how awful, dangerous or deadly. ( The confusions of this high from awful truth also seemed encapsulated by a slogan I’d seen etched on one of the United States G.I. lighters sold on the street in Vietnam: “If you think sex is exciting, try incoming.”)

The lighter I bought on the street: Snoopy saying “Fuck It!” on the front…

…and this slogan on the back…

And yet, as with Conrad’s narrator, something is “not very well.” Nirvana’s generation doesn’t even need its own Vietnam war. They’ve seen enough on TV. The “awful truth”, so commonplace, has overwhelmed us. Kurt Cobain’s screams ride Nirvana’s bouncing pop as if the only sense of joy left is the expression of pain. Bitter disgust has replaced woefully inadequate “normal” reactions of shock and outrage. Perhaps most importantly, unlike Vietnam-era protest music, Nirvana attacks itself. Their music arises from the after-effects of the idealism of self-indulgence, the idealism of youth, the failed promise of rock and roll born as antidote to the repressive 1950’s. Although depressing and not particularly celebratory, this bitterness seems clear-eyed and honest, particularly in a world where the Khmer Rouge have come to represent the evil “other” in the way the Nazis do (in fact, the sign at the Killing Fields calls the Khmer genocide “worse” than the Nazi Holocaust, a judgement Stanley Karnow agrees with in his companion book to the PBS television series, Vietnam). Nirvana rescues us from this void of intellectual relativity. In the Heart of Darkness, their rock and roll screams capture the terror and the tragedy with more resonance. And, ironically, they resonate for precisely the same obvious reason that they’re a good rock band; they rock. They make you move. They make you feel. Or, as they might say on American Bandstand, “it’s got a good beat and you can dance to it.” Your horror is made human.

Perhaps this is why all of the travelers I met liked to quote the Dead Kennedys, saying with a smile that they were taking their “Holiday in Cambodia”, and Phnom Penh’s “Rock Hard Cafe” (not an official “Hard Rock”, but with the same rock star photos on the walls, and which closed during my trip because of the paucity of tourists) even sold shirts with that slogan emblazoned across the back. But it’s a double-edged sword; these catch-phrases act as signposts to identify and even cope with horrific information, but has the sign replaced what it points to? What would Dead Kennedy’s singer Jello Biafra look like in a “Holiday in Cambodia” t-shirt? Or Henry Kissinger for that matter? Most frighteningly, is there a difference? Have they ultimately diluted the experience, and in fact shielded us from our own reactions to it? And isn’t this the understanding at the heart of the punk ethic that tore Kurt Cobain apart when Nirvana achieved pop culture success?

I questioned my own role in all of this when I found myself, an American, a few weeks later in Vietnam, window shopping at the “Wartime Souvenir Shop” in the “Museum of American War Crimes”, and drinking in the Apocalypse Now Bar in Ho Chi Minh City, taking a tour of the DMZ run by a former North Vietnamese officer (“It’s business!” our guide laughed when I asked about ideology, “No problem!”), and sleeping for a few hours in the bed offered me by a former North Vietnamese soldier outside of Hanoi when I got sick from drinking bad water and riding a motorbike all day in the relentless heat. Vietnamese children buy U.S. Army toys all over the country. And they love having their pictures taken, even marching up to you and pointing at themselves, commanding you to photograph them.

Happy kids in Vietnam eagerly posing for a photo from my camera…

Perhaps they’re unknowingly pointing out the key to the issue: our obsession with capturing history as film or art. We’ve tied an invisible loop whereby we create reality just by trying to describe it, like an experiment in quantum mechanics. But we’ve set up mirrors facing mirrors, and we’re tied up in the middle. Meanwhile, we’re distracted from the real event. I still don’t even know if Cambodia was dangerous or not while I was there. The week after I got home, CNN reported an attempted coup by Prince Sihanouk’s own son (causing the U.S. Embassy to cancel its July 4th fireworks for fear they’d be misheard as a revolution in progress).

This mirror game was especially evident on my visit to Angkor, the famous temple complex built between the 9th and 12th centuries, where they say the spirits are most alive. I’d spent days trying to get information on the relative danger of the situation up there, with, as always, conflicting reports. The woman at the U.S. Embassy told me not to go overland, since trains were being blown up by the Khmer Rouge and taxis and boats were being robbed by bandits, but that I’d be okay if I flew, although, she reminded me, “you’re not safe in New York.” People in my guest house said the U.S. Embassy was in league with Kampuchea Air to make money off of my plane ticket, while other travelers told me the boat often got stuck for days in low water. The bartender at the Heart of Darkness told me the boat was okay but not to be on the streets after dark once I’d gotten to Siem Reap. I finally decided to spend the fifty dollars for the plane and was feeling good about having responsibly vanquished the fears from my head as I sat down to dinner at my guest house the night before.

“I hear you’re going to Siem Reap tomorrow” said the man across from me as he ate a huge spoonful of mashed potatoes. He had been a lawyer in Ireland and was now teaching English in Phnom Penh, which was kind of funny since I couldn’t understand him about 30% of the time because of his thick Irish accent. He was a big man, over 6 feet tall, and he looked like Willem Defoe.

“Yiu’re a braver man than I” he said.

“What do you mean?”

He looked incredulous, as if I’d asked what country we were in. “It’s a war zone up there! “ he laughed. “I’ve been all over the world and ye’ couldn’t get me to go anywhere in Cambodia outside of Phnom Penh for a million pounds…could you pass some more potatoes please?”

I actually made it to Siem Reap the next day, although I procrastinated long enough that the owner of my guest house had to race me to the airport himself on his scooter, which had no windscreen, and since no one wears helmets, we both spent the entire half-hour ride squinting and wiping dust and tears out of our eyes with one hand while the other hands were steering and signaling through the crazy traffic, as well as hanging on to my pack, and the bike itself. I was safely checked into a guest house in Siem Reap a few hours later, and that night was drifting off to sleep to the peaceful sound of my fan whirring overhead, content with a recurrent travelling lesson –that there really was nothing to fear once you actually arrived at the reality beyond your own head– when I was awakened by what sounded like either a car backfiring — or a shot. Then another. “Something minor” I thought, utilizing my travelling lesson and snuggling deeper into my bed. Then another shot, and then a round, coming faster and faster and before I knew it there were the explosions and gunfire of a war being fought a block away. I got out of bed and switched off the fan, thinking it might be playing tricks with my hearing, but the gunfire continued. I was struck by the realization that I had been vacationing for the past few weeks in the middle of a civil war. I heard rapid fire Khmer being spoken outside my door, and cautiously opened it.

My hosts looked at me standing in my shorts with big grins. “No problem!” they said, before I could open my mouth, “No Khmer Rouge!” I found out the next evening, from piecing together a few conversations I’d had in broken English, that a police officer who lived down the block had knocked his wife unconscious in a domestic dispute, and when she awoke alone she was so angry she set the house on fire, which set off all his ammunition.

A good story, I knew, but it led to an even better one for the next day. Although I’d never driven a motorbike myself before, I decided to rent one to tour Angkor. Small town Siem Reap traffic wasn’t as crazy as in Phnom Penh and my own bike would give me more independence, not having to haggle over prices and depend on other drivers for rides. Although wobbling in stops and starts at first, I managed to avoid causing any accidents and my confidence improved as I rode all day, from Siem Reap to Angkor and then through the vast temple complexes. I made it all the way to the deserted temples at the far end, and then snapped one last picture and hopped on my bike as the sun was going down, heeding the bartender’s warning to get back to Siem Reap before dark. Halfway through the winding paths of Angkor the bike suddenly sputtered and died and came to a heavy stop. It wouldn’t start again.

I was alone opposite the Bayon, a temple described by the book I’d bought from the kids at the Capitol as “famous for its forty-nine towers carved with gigantic faces on each of their four sides, all with enigmatic smiles leering down from the tops”. The Bayon loomed on my left and a huge statue of the Buddha looked calmly down from the jungle on my right, with me in the middle on my broken-down motorbike, as the night came on and the crickets whirred like an out of control air-raid siren. The endless eerie smiles reminded me of the bartender’s smiling warning at the Heart of Darkness and the neatly stacked rows of smiling skulls at the Killing Fields, and I flashed on my own worries about learning to ride a motorbike with no helmet or traffic laws, and all of the terrifying stories about the Khmer Rouge I’d heard in the last few weeks in my attempts to get any clear information at all about what was going on in Siem Reap, or Cambodia for that matter.

My thoughts were interrupted by a loud gunshot. A bead of sweat trickled very deliberately and coldly down my spinal cord and for the first time in a month of traveling through tropical heat I actually shivered. The encroaching darkness was making the lines on the faces of the Bayon more distinct. I heard another shot and when I looked up those mysterious stone smiles seemed to reveal their mystery: the temples knew and they knew with calm confidence; you’re not in control, they smiled. There’s something here that simply dwarfs you. It’s just here. It always is.

The United States got involved in something strange in Southeast Asia. We jumped with our eyes closed right into those smiles and we just kept falling. As with Conrad’s natives, the placid smiles became mirrors reflecting ourselves. The jaws of our own mystery slowly widened until ideologies and ideas and everything burned away to the Heart of Darkness. And where has this self-confrontation led? Now we go back to it, or read about it, and it’s a bar and a T-shirt; this is of course what we’ve asked for and its echoes reverberate far beyond Nirvana’s screams from the blackness of the bar: “Here we are now, entertain us!”

We can’t fault the Cambodians for taking people to see the Killing Fields. We all need to make money, and we all want to be in a movie.

But I feel as if I finally glimpsed a reality behind the movie, between the mirrors. In some bizarre way, it all came together in that bar when a punk band from Seattle somehow inadvertently expressed the feelings engendered by the situation in Cambodia. As if the distance of half the globe allowed me to catch a moment in May 1994 when Nirvana was simultaneously destroyed and empowered by its own suicide mythology, and thereby hung suspended above its commodified illusion. As if Nirvana’s global popularity was that trembling reality waiting to fall, evidence of the universality of their expression of our present state as epitomized in its darkest form. Kurt Cobain transformed the Buddhist negation of the self into the literal killing of the self. You can see it in the way he smiles at the end of the video for “Heart-Shaped Box”. Not the smile of the Buddha, serene in the knowledge of the illusion of the self , but, cursed with an extreme empathy in this shrinking world, the painful knowledge of the self as evil. And, like Kurtz, it knows it’s evil.

A Cambodian farmer appeared out of nowhere and for one dollar silently knelt down and adjusted something to bring my bike back to life. I made it back to Siem Reap in the dark and eventually back home to the States. Although now two years have passed while I’ve lived my life here in sunny California, another part of me is still sitting on that stool, hearing Nirvana in the Heart of Darkness.

I drank another beer in the dark heat of the bar, and this mixed metaphor flashed before me: Did Kurt Cobain sing like the canary in the coal mine, balancing at the tip of an iceberg, leaving us collectively bound to follow, inevitably falling prey to our own commodified mythology? To get beyond the myth, how are we to respect reality and the art which creates it? It seems that the much-lauded Schindler’s List, which was playing to packed houses before I left for Asia, doesn’t approach the real evil behind the Nazis. It’s easy to say the Nazis were monsters, but so were the Khmer Rouge, and the British in Africa, and prejudice and closed-mindedness everywhere, even in our own reflections. Nirvana clawed its way to this horror, while remaining aware of its unique spawning nature: the danger of horror as commodified and thereby conquered; their music knows and still feels the absurd tragedy epitomized when Robert Duvall proclaimed at West Point his famous line from Apocalypse Now: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” and the cadets cheered!

Kurt Cobain says on the liner notes to “Insesticide” that he doesn’t want homophobes, racists, and other closed-minded people to be Nirvana fans. But they were, and Nirvana was marketed and Newsweek ran its perfunctory cover story on youth suicide. And Kurt’s suicide note is laden with the weight of culturally constructed mythology: feelings of guilt at not being able to appreciate his celebrity position “like Freddie Mercury” had and ending with the “Better to burn out than fade away” line from Neil Young.

And the latest news is that those three Westerners kidnapped on their way to the beach were killed not by the Khmer Rouge, but by the Cambodian Army. And maybe they were running heroin.

I realize now that sitting in the Heart of Darkness, as Nirvana blared out over the speakers, I was hearing something like Conrad’s Kurtz, like a real voice crying out the final death of civilization.

“He had something to say. He said it. Since I had peeped over the edge myself, I understand better the meaning of his stare, that could not see the flame of the candle, but was wide enough to embrace the whole universe, piercing enough to penetrate all the hearts that beat in the darkness. He had summed up – he had judged. “The horror!” He was a remarkable man. After all, this was the expression of some sort of belief; it had candour, it had conviction, it had a vibrating note of revolt in its whisper, it had the appalling face of a glimpsed truth – the strange commingling of desire and hate.”

But it’s not “the horror” anymore; we’ve seen too much of it. “Oh well, whatever, nevermind…” Nirvana sings. A sense of tragedy and pain, but unlike Kurtz’s vision, not only is it not a shock, it’s not even mildly surprising. And maybe that’s why Kurt was already dead. Nirvana occupies a tenuous position between urgency and nihilism. But why hang on when there’s no difference anymore between a bang and a whimper.