There’s an interesting cinema verite scene in the otherwise painfully-dated-except-for-the-concert-sequence movie “Rainbow Bridge” where Jimi Hendrix is talking about a dream or vision he had – he describes souls gathered in outer space like cattle at a watering trough and then venturing into the world, being with a soldier in Vietnam, and then returning to the trough.

(In the grand tradition of Andrew Marvell’s famous seduction poem, “To His Coy Mistress”, Hendrix’s soul then flies back in time to Cleopatra and tries to convince her to “forget all her hangups and get a vibe” with him).

But it’s the first vision that sticks with me. Hendrix’s souls in outer space are connected with each other and the souls on the planet. They first travel to a soldier in need, immediately full of a natural empathy and compassion. This visionary sense of interconnectivity is perhaps THE essential theme running through all spiritual traditions.

Hendrix’s vision reminds me of a Blackfoot Indian myth concerning an ancient pact made between the Blackfoot Tribe and the Buffalo.

Very briefly: In an earlier time, the Buffalo refuse to be killed, a young Indian woman tries to trick them and is instead kidnapped by them, her father is killed looking for her, and she weeps until the Buffalo allow her to bring him back to life with a song. The head Buffalo (embodying the mythic spirit of the Buffalo herd) then teaches the young woman a ritual song in which the Indians are to dress and move like the Buffalo – this will be “the magic means by which the Buffalo killed by the Indians in the future are to be restored to life.”

All very trippy – yet very real and practical. It is vision leading to Right Action.

Because the point is that when the girl mourns for her father she understands the sacrifice the Buffalo make when they lose their loved ones. And the ritual then is a means by which all the Indians in the future are also forced to identify with the Buffalo.

This works internally – when you play act, you identify with (and you respect), so you are probably less likely to indiscriminately slaughter yourself, at least not without some serious thought.

It also works practically. If you had to dress and dance around like a cow everytime you wanted a hamburger, would you have the time to be able to conveniently eat so much “fast food”?

So although the Scullys of our age may write off the belief in this myth as silly, and the ritual as superstitious – it not only exhibits an understanding of the interconnectedness of the Indian and the Buffalo (the eater and the eaten), but it has the desired real world practical effect of bringing the herd back to life.

The Indians do not indiscriminately kill Buffalo for sport or fun while drunk, or waste most of what they kill. The way the more “enlightened”, non-superstitious, non-ritual-practicing, everything-is-separate-and-here-for-my-pleasure white man did.

The herd is not killed off. They can regenerate. They are “brought back to life.”

I never thought I’d quote Ted Nugent in this column, but I’ve got to admit he got it right in “The Great White Buffalo”:

“Well, it happened long time ago,

in the new magic land.

The Indian and the buffalo,

they existed hand in hand….

The Indian needed food,

he needed skins for a roof.

But he only took what they needed, baby.

Millions of buffalo were the proof”

(writer’s note: Terrible Ted’s “Stranglehold”, “Cat Scratch Fever” and “Wango Tango” are probably of less kinship to Right Action…)

As Ted proclaims, the proof is in the Buffalo pudding – the Blackfoot’s understanding of interdependence results in lots of Buffalo and therefore lots of Indians – the souls are gathered at the same watering trough –

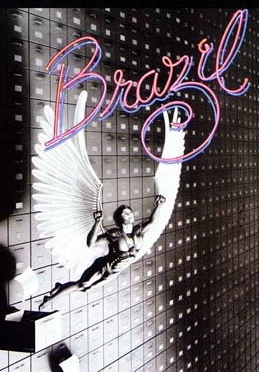

“We’re all in this together” Robert DeNiro’s outlaw freelance repairman proclaims, striking the only hopeful chord in Terry Gilliam’s quite hallucinatory (the tag line was “It’s only a state of Mind”) “1984”-ish, 1985 film “Brazil” – although this doesn’t ultimately help Jonathan Pryce’s embattled protaganist survive against the repressive, monolithic, bureaucratic powers that be.

But perhaps with a little song and dance…

Someone throw that man a guitar – or a boombox – or an iPod.

But someone did. The title of Brazil comes from the main character’s feeble attempts to buck the system through listening to music – according to Terry Gilliam the character listened to “strange Latin escapist songs like “Brazil”. The music transported him somehow and made his world less gray.”

Why are his attempts “feeble” then and why does he fail? Perhaps because the music is only “escapist.” No follow-up. No Right Action.

The Blackfoot ritual is certainly not escapist – on the contrary, it is a song and dance that brings the tribe face to face with the reality of killing – they appreciate the significance of the sacrifice – that it’s not just another…um, happy meal.

“We’re one, but we’re not the same, we get to carry each other” sang U2 in 1990, connecting responsible action into the vision of interconnectedness.

Obviously, U2, Hendrix (and Mr. Nugent) (discounting, of course, the rest of his oeuvre), and many others mentioned in this column past, present and future, also use song as more than escape, as magic.

It’s why the jam matters.

Consider the original concept of “Brazil”:

“It would feature an oppressive, totalitarian government which systematically stripped the public of its basic freedoms in favor of an ostensibly fraudulent and hopeless war on terrorism…

…the mechanics and systems of this “fantastical” world would need to be absurd and contradictory, serving only to bury its chief directors under bureaucracy, red tape, and endless coils of administrative paperwork. Identification cards, DNA scans and security checkpoints would round out Gilliam’s view of a monolithic, technologically-driven society, and patriotic propaganda posters telegraphing a mandatory us-or-them mentality would be broadcast regularly to all citizens amidst the false cheeriness of a consumer theme park culture.”

Hallucinatory, yes, but prescient. Which is why, today, the jam REALLY matters.

(And in another serendipitous synchronicity, the producer of Brazil called his movie “the biggest production since Cleopatra” – so maybe Jimi’s soul has again left the watering trough, and somewhere he’s finally getting his vibe…)